The Current Status of Ocean Energy: Offshore Wind Blowing Strong

5 min read

Oceans contain nearly 1.5 billion cubic kilometers of constantly moving water. That in itself gives a sense of the sheer of the seas and the large amount of energy that can potentially be extracted. While ocean energy holds great promise, the technological challenges for harvesting it are daunting.

© Getty/Alvarez

A Harsh Marine Environment

Ocean energy, often called , refers to renewable marine resources. It includes tides, currents, waves, sea winds and water temperature differences. The ocean’s abundant can also be harvested to produce power.

The promise of all this potential power has spurred research on converting ocean energy into , particularly during the first decade of the century.

But efforts have been hampered by a host of marine environment issues, including the challenge of installing equipment on the seabed, maintenance costs (response boats need to intervene in the absence of digital remote solutions) and fragile ocean and shoreline ecosystems. In addition, seawater causes rapid of underwater structures and biofouling, or the accumulation of microorganisms (mainly crustaceans) on artificial surfaces. One answer is to make materials sufficiently robust to survive aggressive ocean conditions.

Offshore Wind Takes Off

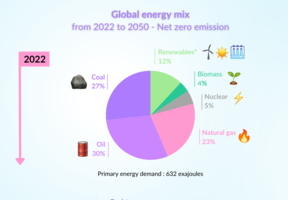

One ocean energy that stands out from the others is wind. In 2018, it accounted for 0.3% of worldwide power generation, and although this may not seem like much, capacity could increase 15-fold by 2040, according to IEA experts.1 The advantage of offshore wind is that it is deployed in large areas – usually more than 10 kilometers from the coast – and uses turbines that are significantly taller and more powerful than their counterparts. In 2020, the world’s largest turbine had a 222-meter rotor diameter and a capacity of 15 megawatts, compared to an average of 2 megawatts for an onshore turbine.

A growing list of countries (China, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, the United States, and soon, France) have embraced offshore wind development. Floating wind turbines, which can be installed farther offshore, are becoming more popular.

Tidal Energy

Tidal energy, which captures the movement of tidal flows in estuaries, is the oldest form of ocean energy. France was a pioneer in this area, having built a on the La Rance estuary in 1966. The station has an of 240 megawatts, which is modest in comparison to that of a high-efficiency, gas-fired power plant (600 megawatts) or an average (1,300 megawatts). To dam the river, a massive, 750-meter-long barrage was built across the estuary, causing significant disruption to the surrounding coastal ecosystems.

In 50 years, only the Sihwa Lake station in South Korea has managed to generate more power than La Rance, but only by a few megawatts. South Korea and the United Kingdom have plans to build 1,300 or 2,000 megawatts power plants, but these projects have been stalled mainly due to environmental opposition.

Other Ocean Energy Technologies

A few tidal farms, a term applied to wind and solar parks as well, are already sending electricity to the grid. One such project, situated off the north coast of Scotland, operates turbines with a capacity of 1.5 megawatts. Paimpol-Bréhat, a demonstration farm in France that conducts turbine tests, is also studying the energy potential of the Alderney Race, at the tip of the Cotentin peninsula in Normandy. Location is a crucial factor of energy output: At the Alderney Race, the current can run up to 12 knots (22 kilometers per hour) during equinox tides.

In the field of wave energy, arrays of articulated, serpent-like devices were tested off the coast of Scotland and Portugal for several years. The projects have since been discontinued but other techniques are being tested. As for the other ocean energy technologies, they are mostly in the research or prototype stage. The difficulty is often one of scale: Some sectors, for example, have begun cultivating algal biomass for the small-scale production of high value-added products. Currently, however, the mass-production of algal and biomethane is still at the research and development stage.

1 See International Energy Agency report